I’m starting to get a feel for this new year we’re in and I’ll share my prediction that it’s going to be like that description from the film Ghostbusters: “Human sacrifice. Dogs and cats living together. Mass hysteria.†Or so it will seem while we’re in the midst of it. By 2017, I’m sure we’ll all look back on it with fondness, but until then buckle in for a wild ride.

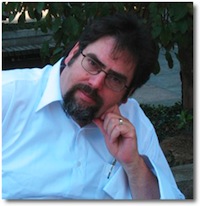

Or maybe it’s just me. Anyway, don’t let that deter you from meeting this week’s EATING AUTHOR guest, Jason Gurley, whose novel, Eleanor comes out tomorrow. Jason actually self-published it back in 2014, and look how that turned out for John Scalzi, so fingers crossed, right?

In fact, he’s self-published four novels, including Greatfall (set in Hugh Howey’s Wool world), and he’s on record as saying some of the most intelligent and cogent things about the whole indie experience that I’ve ever heard from an author. Keep your eye on him, he’s got the real stuff, as evidenced by the following description.

LMS: Welcome, Jason. Let’s dive right in, tell me about your most memorable meal.

JG: I spent far too long considering this question, attempting to remember the best execution of each of my favorite dishes, before I ran into the perfect answer. Some of the answers I considered before doing so: my wife’s modern interpretation of the kolaches I grew up enjoying; the childhood chicken-and-dumplings dish that my mother used to make, but now cannot remember the recipe for; the chicken pot pie I attempted to make for Felicia (my aforementioned wife), over which I slaved incompetently for eight or nine hours, until we finally ate it (and were utterly disappointed in it) at ten p.m.

But the perfect answer is: gallo pinto, at a resort hotel on the southern coast of Costa Rica. It’s not the perfect answer because it was the most delicious food that Felicia and I have ever eaten (though it was staggeringly delicious); it’s the perfect answer because it was our first meal after a journey we thought might end in our very premature deaths.

I’m not even tempted to downplay what I just said, either. Even now, five years after the story I’m about to tell you, I still remember just how damn sure we were that we wouldn’t live through the night.

In 2010, Felicia and I were married on the patio of a friend’s beautiful wine bar in Arroyo Grande, California. We’d been engaged for a year, together for nearly four, and the wedding was everything we wanted it to be. No church; wine bar. No minister; Internet-ordained long-haired metal-rock-god buddy instead. No seven-tiered cake; Felicia’s favorite toffee cake from a local bakery. No three-course meal; instead, a breakfast buffet with biscuits and gravy and eggs and bacon! No Bible verses were read; instead, Ann Druyan’s remarks about her marriage to Carl Sagan were shared. (We’re as dorky as anybody, see.) We’d worked hard to save money and pay for the day ourselves. And all of this is important because as soon as it was over, we thought our lives were, too.

We’d booked a getaway in Costa Rica, at the Hotel Punta Islita. Despite Felicia’s proclivity to airsickness, we hopped a plane: first to Los Angeles, then to Houston, then out of the country to Liberia, Costa Rica. Our plane landed around one a.m., in the middle of what we quickly discovered was monsoon season. We shuffled through customs in a building with no walls, watching lizards zip across sidewalks, dodging marble-sized raindrops. We knew we’d be arriving at the hotel very late; it’s a nearly three-hour drive from Liberia’s airport to the hotel. The hotel assured us that someone would be there to receive us, even at four in the morning.

Our driver might not have been human. He looked human, but he drove like a demon, or, more appropriately, he drove like someone who had never been in a moving vehicle before. The vehicle in question was an airport shuttle bus. We dutifully waited as he dropped other travelers off at nearby hotels; when the bus was empty except for the three of us, he glanced up in the mirror and said, “Punta Islita, right?†We nodded. He sighed. And then we set off in the dark.

The city streets quickly became mountain passes. He took every slick curve thirty miles an hour more quickly than he should have. On every wild turn, I was convinced the bus would leave the ground. Felicia fought her motion sickness; I fought my own irrational fear and tried to assure her we’d be okay. She ended up assuring me.

As the hours passed, the night grew blacker. There were no lights on the roads, just jungle foliage as high and deep as we could see. The rain didn’t let up; it fell harder, and the roads were washed over by mud and rising water. Eventually, having failed to die horribly in the mountains, we descended into lowlands, where we were horrified to see entire families walking along the road, carrying their belongings and leading donkeys and other animals by ropes. Their homes were flooded, the water as high as their doorknobs. We crossed a bridge and the driver shook his head worriedly. “The water is never this high,†he told us, and we looked through the windows to see the bridge barely clearing a brown torrent that swept just below us, dragging an awful lot of debris with it. “The bridges ahead might not make it.â€

We didn’t say anything yet. Surely there were alternative routes, if the worst happened. But hours into the journey, the driver braked and stopped the bus. We’d passed someone’s car, swamped on the side of the road. The road was rutted and rough and beginning to disappear. And now the bridge ahead was in the process of washing out. I jumped out of the bus with the driver, and we started attacking broken tree trunks and limbs that had fallen across the bridge. We dragged them aside, trying in vain to clear a path, and we might have succeeded, if the driver hadn’t put a hand on my shoulder and stopped me. He pointed at the river below the bridge. It almost wasn’t below the bridge any longer: the debris it carried was backing up as it collided with the side of the structure, and large, dangerous fragments of it tipped over the bridge rail. Gushes of mud and water and broken things spilled across the bridge in front of us.

On the other side of the bridge was darkness, a long jungle road just like the one we’d been on for the past several hours. But twenty or thirty minutes farther along that road was our hotel, with its clean sheets and running water and food, and honeymoon memories waiting to be created. We’d thought about Belize, back when we were considering destinations, but the timing wasn’t great. It was Belize’s monsoon season, the guides indicated.

Belize sounded pretty good right now.

The driver and I got back on the bus, where Felicia was waiting, worriedly, and the three of us watched the bridge ahead clog with debris and fill with water. “What now?†we asked the driver, who said, “There’s a town back there we’ll go to. You can stay the night, and call a driver tomorrow.†We asked if tomorrow the roads would be any better than they are now. The driver cheerfully said that of course they’d be fine for driving on tomorrow. Neither of us believed him.

He turned the bus around — not an easy task on the narrow jungle road, with rising water obscuring ditches and holes — and we backtracked for an hour to a town we hadn’t even seen in the darkness. It was four or five in the morning, and the place barely resembled a town. The driver parked the bus in front of a building that he said was a hotel. It was pitch-black, with no sign of life, but the driver climbed out of the bus and shouted something, and a voice responded from the darkness, to our surprise: a bored-looking fellow manned the outdoor front desk.

Tired, disappointed, and relieved to not be dead, we followed the bored man to our temporary hotel room. The storm raged on outside, and our shuttle driver waved and disappeared. I assume he made it back safely to Liberia. He seemed quite capable of cheating death.

In the hotel room, Felicia cried. It was terribly hot inside. The place was ramshackle at best. We spotted cockroaches on the floor, a gecko fastened to one wall. A lazy ceiling fan did nothing to disturb the heavy air. We were suspicious of the bed, which didn’t appear to have been tidied up before our arrival. Our honeymoon was off to a terrible start, and we found it difficult to even think about a pleasurable vacation after having seen so many displaced families en route.

We hardly slept. We’d seen entire hillsides collapsing into muddy rivers on our way here, and it was so dark outside the hotel that we couldn’t be sure our room wasn’t directly in the path of some dark jungle mountain that might give way at any moment and sweep down upon us. We hadn’t eaten anything in hours. We were irritable, worried. We’d been married for a day and a half.

In the morning I wandered through what I now saw was a good-sized small town, looking for a telephone. Our cell phones couldn’t find a signal. There was an internet cafe, if you can believe that, just beside the hotel. It didn’t open for hours, so we waited, and then it didn’t open at the appointed hour, and we waited longer, wandering around the town a while first. There wasn’t much to see. The town wasn’t thriving. When we realized we’d walked in a figure eight and seen everything there was to see, we returned to the internet cafe, which had finally opened. We called the resort hotel, and they were worried about us, since we hadn’t arrived. We didn’t need to explain why; we just needed to tell them where we were. We didn’t know. I had to ask the bored woman behind the cafe’s counter. The hotel said they would send a driver to get us, and not to worry: there was a safe path to the hotel. “One hour,†they said, “and you’ll be here, and everything will be wonderful.â€

While we waited for the driver, we checked out of the temporary hotel — which looked deceptively nice in the daylight — and walked to a nearby restaurant with our bags. There were no other customers. We were seated at an open-air table, under another lazy ceiling fan, near a television that played orange soda commercials in Spanish. We were exhausted, confused, and far from optimistic. When the server came to our table to ask what we would eat, Felicia asked her to recommend something. The woman asked if we were visiting Costa Rica. It seemed obvious that we were, but we just nodded. She said, “You have to have gallo pinto. It’s a real Costa Rican breakfast.â€

We agreed. I’m not even sure we knew what we’d ordered. As we waited, we started to decompress, just a little. We hadn’t died in a mudslide or a bridge collapse. We’d survived the night, despite our driver’s best efforts to kill us. The hotel had things under control, and was sending a driver to retrieve us. We’d lost a day of our honeymoon to the weather and bad roads, but we tried to cheer each other up: we still had several days remaining, and the rain had stopped sometime in the night, and in an hour we’d be checking into our room at the beautiful resort we’d booked online.

The food arrived. I’m a fairly finicky eater — a ‘selective’ eater, Felicia kindly corrects — and I’m always suspicious of new foods. But this gallo pinto the server had brought us — why, it was simply black beans and rice, with accompanying scrambled eggs and bacon and a plantain tortilla or patty or something. It looked and smelled delicious, and we dove into it. The food told us that we were safe after all; everything really was going to work out just fine.

The driver took his sweet time arriving. We found out why, once he did. He wasn’t a hotel employee at all, but a freelance off-roader they’d hired to come get us. He arrived in a battered Toyota 4-Runner. The “safe path†the hotel people had described was a rutted jungle trail that wound high into the mountains, above the worst of the mudslide devastation and flooded rivers. When he left the main roads, steering us into the jungle, Felicia and I just pretended we weren’t worried, and went along with it. We passed gaunt cows high in the hills, and looked down steep cliffs at distant ribbons of rivers. The driver pointed out the bridge that had stopped us the day before. It looked as if it had been fractured by the mudslide; the entire hillside above it was stripped bare, just a raw wound of wet earth.

At last, after ninety minutes of roundabout mountain off-roading, the 4-Runner burst out of the trees and onto a tidy, paved road. We watched in relief as the road curved uphill, passing a sign for the hotel resort. The rain started again, but we weren’t worried anymore. The driver carried us to the top of the hill, and Felicia and I watched a man in a white shirt and white pants walk out of the hotel, smiling. His attitude and posture said the same thing our gallo pinto breakfast had: You’re safe. Everything is okay. Look, you made it.

We were grateful. The hotel employee might as well have been a winged angel. He guided us into a lovely hall, offered us glass-bottled Cokes, ice-cold, and went to get our reservation papers. The Cokes were the best we’d ever had. We were alive. We’d made it.

The resort was practically empty except for the two of us. We had the run of the place. But every morning, before we did anything else, we wandered down the hill to the resort’s seaside restaurant, where we sat and watched the brown sea, filled with mud and runoff from the storm, turn blue over the next several days. The sun came out, the rains stopped, and we ate gallo pinto for breakfast each and every morning until it was time to leave.

All marriages should start out with death defying adventures. It’s a good anchor to have as you go forward in life. And the gallo pinto sounds great too.

Next Monday: Another author and another meal!

#SFWApro

Tags: Eating Authors