The Hugo finalists were announced this month, which of course means I immediately began scrambling to continue this blog’s time honored tradition of contacting all the nominees for the Campbell Award for Best New Writer — something I’ve done for seven years now — and invite them to share the telling of their most memorable meal. And, as sometimes happens, one of this year’s nominees, Ada Palmer, has already been here (last May, in fact). I’m still waiting to hear back from nominees J. Mulrooney and Laurie Penny and I hope they can spare the time for us all. Nominees Malka Older and Kelly Robson have already responded to my queries and will be featured here over the next few Mondays (with a possible break for another author with a debut novel), but we start with today’s EATING AUTHOR guest, Sarah Gailey.

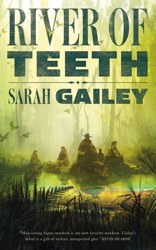

You’re more likely to know here for her nonfiction — she’s a frequent essayist for Tor.com and a past nominee for the Best Related Work Hugo Award — but that’s probably going to change when River of Teeth comes out next month. And check out her website where you’ll find links to a wide assortment of her shorter fiction.

LMS: Welcome, Sarah. Tell me about the most memorable, the very best meal you’ve ever experienced.

SG: The best meal I ever ate was in Belize, in 2014, outside of a cave that had a princess’ skeleton inside.

I’ll explain.

The cave is called Actun Tunichil Muknal — the Cave of the Crystal Sepulchre. It’s also known it as “Xibalba†after the Mayan underworld. A long time ago, it was believed to be an entrance to hell. I paid a man some money and he led me through the Tapir Mountain Nature Reserve to get to the cave. We walked through the rainforest, not seeing any creatures beyond the fish in the river. I’m sure we were seen by many, though. He convinced me to taste a leaf from the quinine plant, which was so bitter that he laughed until tears gathered in the corners of his eyes. We waded through the shallower parts of the river. I looked for snakes, which he told me I wouldn’t get to see, because they didn’t want to be seen by the likes of me. He cut some branches away from the path with a machete — more for show, I think, than for utility. We could have ducked under them.

We stopped outside the cave, which looked to me like a lake. There were some wooden benches there. My guide left our pack under one of them and dove into the water. I swam after him, my hiking shorts billowing behind me in the water. A huge pale fish swam under me for a moment, then disappeared to a depth I couldn’t see.

We swam and walked through the cave, and my guide told me stories of the Mayan underworld — of the gods of corn and rain, of the levels of hell, of the courage it took to enter the caves back before headlamps existed. He stood with me in one empty chamber with a ceiling almost too high for the beam of my headlamp to reach, and he had me turn the light off. I have not been afraid of the dark for a long time, but it was so dark in the cave that my heart immediately clenched with terror. The guide put his hand on my arm and we stood in silence, listening to the water and the minute sounds that sleeping bats make.

When we reached the site of the sacrifices, I had to take off my shoes and put on dry socks. No shoes allowed on the rocks where the sacrifices were made. We walked from ancient pots to ancient pots, and my guide explained what those ancient Mayans sacrificed — corn, and alcohol, and blood. And then the guide shone his flashlight next to my foot, and there, not a meter from where I was standing, was a skull.

We walked on, and there were bones everywhere. The guide told the stories of the human sacrifices, of the drought and famine that drove their communities to bring them to this place that they thought was the entrance to hell. Some of them had been tied up; some, struck across the back of the head. Some were children with long, narrow skulls that had been carefully shaped by parents who loved them very, very much.

We passed all of their bones. We crouched and shuffled and squeezed ourselves into a narrow vestibule, and there she was.

The Crystal Maiden.

He said she was a princess, although I couldn’t help wondering if she was really a princess or if that was just a handy bit of narrative. Some of her vertebrae had been crushed, and then she had been thrown to the ground in the very back of the part of the cave system we were in. Over the years, water flowed gently, slowly over her body, and it left behind minerals. Those minerals grew, the way that she would never grow again. Her skeleton glinted like found treasure in the beam of the guide’s flashlight. This, he told me, had been the last best hope of the people.

I asked how long she’d been there. “A thousand years,” he said. “We don’t take things away, the way you do in America and Canada and Britain. We leave things where they belong. These aren’t just artifacts, they’re history. Context matters.”

He showed me other parts of the cave — the infant sacrifice cavern, full of tiny femurs, and a cavern of pillars formed by the joining of stalactite and stalagmite. And then I put my shoes back on and he led me out of the caves, past white crabs and sleeping colonies of bats. A pebble got stuck between the arch of my foot and my sandal. It was the only thing I kept, and that by accident.

After we swam out of the cave system, we walked back to our packs. I stripped my shirt off and hung it on a tree to dry, and my guide did the same, and we straddled a bench and ate turkey sandwiches and chips and drank water while my guide told me about armadillo season. The armadillos, he said, watch the ground for grubs — and up in the trees, the jaguar watches the armadillos.

The turkey sandwiches were really damn good. No mayonnaise, but baby lettuce and white, crumbly cheese. The water was fresh and warm and a large blue butterfly landed on my shirt to spread its wings. As we walked back, it started to rain — warm, tropical rain — and my guide handed me an orange. I tucked the peel into my pockets, and my hiking shorts smelled like orange oil and cave water for the rest of the trip. Between the orange and the sandwich, I ate like a king that day.

Thanks, Sarah. “Context matters.” Words to live by. Also, “armadillo season” is a phrase that will linger with me.

Next Monday: Another author and another meal!

#SFWApro